Playing around with old ASIC designs

As an old Atari ST owner, I have always been very interested in various retro projects involving that old machine. I’ve spent hours playing around with emulators, reading about various clones and reimplementations, and even gotten more or less tangentially involved in some open source software projects related to the platform.

I got very excited when I discovered that a some of the custom ASIC designs created by had been uncovered and even converted to PDF files by Christian Zietz.

I downloaded the repositories, read through them and then almost immediately forgot about them.

Hacking the MMU

Recently, I took part in a discussion on the Atari ST and STe Users facebook group. Chris Swinson shared an old design posted on Atarihacks, that seems to hack in support for addressing more than the maximum 4MB of RAM possible by generating the missing DRAM signals from pins 23 and 22 on the CPU. Although from the discussion, people who have tried building it never actually got it working, but it seems to be almost possible, baring timing issues with the design.

But it’s not quite as simple as that. The CPU isn’t the only hardware that needs to access the DRAM. The Blitter does too and seems to have the necessary address pins to address the full address space. However, the DMA and the Shifter don’t generate any address signals at all. MMU has internal registers for managing the current address for the video buffer sent to the Shifter, and another set of register for DMA transfers, and since they are internal to the MMU, there is no way to add the missing two bits of address to them without replacing the MMU with a new implementation.

Enter the schematic

And this is when I remembered the ASIC designs. In a moment of hubris I though I would take the entire design and translate it to Verilog. Then one could find a suitable CPLD and create a functional clone of the chips ready to paste in. Following Chris’ work on overclocking the ST, the MMU and GLUE chips could even be enhanced to support faster and more RAM, utilizing the full 24 bits of address space supported by the M68000!

Now, there are at least a few problems here. Firstly, I’m completely new to HDLs and everything about reconfigurable hardware such as CPLDs and FPGAs. This means I’m learning to write Verilog at the same time as learning to read the schematics. – I really do like jumping in at the deep end :).

So I decided to start slowly. I opened up the schematics for the combined GLUE/MMU ASIC in the Atari STE (as that is the only version I have access to), and after some initial browsing, I found out that page 2 was part of some relatively easy to grasp address decoding. I could “simply” trace back from the pads and stitch together how they were activated.

Hand-written logic designs like the ones create by Atari are extremely low level. There seems to be some macro support in the tool used, as I noticed that some of the counters and registers use blocks defined later in the document, but most of the address decoding used mostly simple AND, OR, XOR gates, buffers and inverters.

It started simple. After getting used to that the designers liked to string together multiple NOT gates (possibly for buffering or some delaying, I assume?), I figured out that the /RAM pin of the chip was activated when it saw an address in the range 0x000008 to 0x3FFFFF.

When in ROM…

That was promising. Next came the /ROMx pads. I immediately noticed that there were way more /ROMx select signals on the GST MCU than on the original ST GLUE package. And that was despite the STe actually used fewer ROM select pins than the ST.

The ST originally used three pairs of 32KB ROMs for a total of 192 kilobytes of TOS. In later models it had already been replaced with larger ROM chips and some TTLs merging the /ROM0, /ROM1 and /ROM2 signals. The STE relocated the ROM from the original 0xFC0000 base address to 0xE00000 to make room for a larger 256KB ROM, which is selected by the /ROM2 signal. The /ROM0 and /ROM1 pins are unconnected, but from the ASIC schematics, I learned that they map to 0xE80000 to 0xEBFFFF and 0xE40000 to 0xE7FFFF respectively. This allows the STE to potentially address 768 kilobytes of ROM in total, if these pins were made available.

Before talking about the cartridge ROM pins, /ROM3 and /ROM4, I took a look at the new /ROM5 and /ROM6 pins. I traced these to map to two different halves of a 512 kilobyte address area from 0xD00000 to 0xD7FFFF. (With the lower numbered pin mapping to the upper half as in the other cases.) Searching the web, it seems that by probing the address space of the STE, this was already known, but I haven’t yet found any explanation why these pins were added.

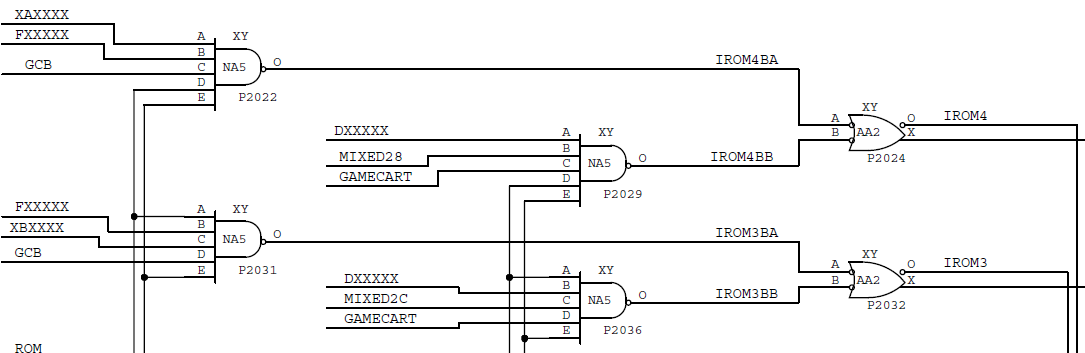

GAMECART?!

This is where I made a small discovery. The decoding of the /ROM3 and /ROM4 pins used on the ST and STe to select the cartridge port ROMs had some extra logic in there. The first part still mapped to the traditional 0xFB0000 and 0xFA0000 address spaces, but the second part was very interesting. Controlled by a signal called GAMECART, these pins could optionally be made to map to 0xD80000 to 0xDFFFFF, making that mysterious unused ROM area a whole megabyte!

The name of the signal may serve as a hint. Did Atari plan to include a larger game cartridge on the STe, or did they plan to release a game console based on the same hardware?

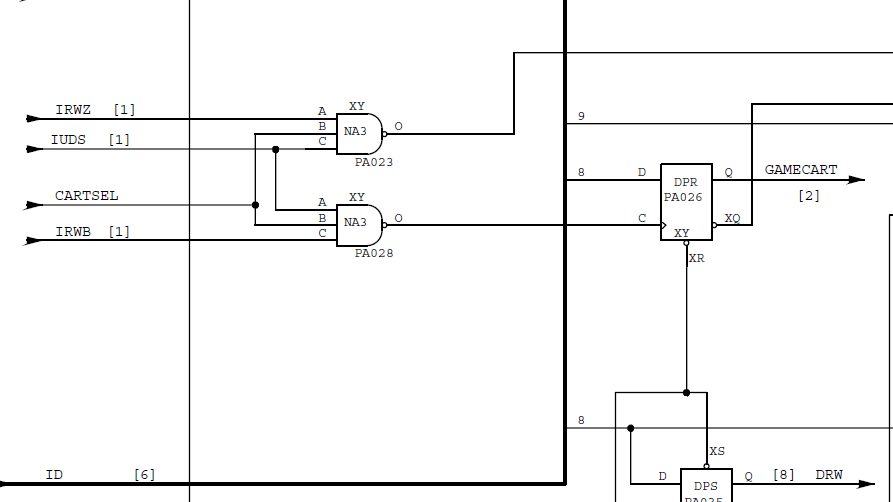

How is that GAMECART signal created? I traced it back to the section in the image at the top of this article on page 10 of the schematics. The signal comes from a flip flop, that is set by writing to bit 8 on 0xFF9000.

I don’t own an STE, but it would be interesting to see if someone could do a quick test to see what happens by writing byte 1 to address 0xFF9000. Does it relocate any connected cartridge to 0xD80000?

Final thoughts

This is how far I got. I’ve written a few modules of Verilog performing the basic address decoding uncovered above, and another for some of the clock signals generated. Simulating the modules allowed me to verify that the signals were getting activated with the given input signals.

But after all this I might not need to decode the entire design. Chris Swinson reminded me that there are multiple FPGA implementations of the ST available. The Suska project even was developed by replacing the hardware on a real ST motherboard piece by piece and seems to be fairly accurate.

Performing this kind of detective work may be useful for projects like these and even emulators. As seen above, it can uncover hitherto unknown hardware features and bugs, allowing for more accurate emulation of the original systems.

I might still end up creating a SUPER-MMU implementation in a CPLD. But there is a long way still. And it’ll require me to play around with actual hardware, which is not my strong point yet. And any decent CPLD or FPGA with enough pins come in awesomely hard to solder packages. I better practice my soldering skills some more. :)

Update

Literarily minutes after sharing this article on the Atari ST and STe users Facebook group, Troed Sångberg pointed out this thread on atari-forum.com posted by Christian Zietz himself, discussing the very same internal GAMECART register and implications.